By Tory Bruno

Orbital debris has become something that we must urgently deal with. It is not tomorrow’s problem. It is today’s issue. Fortunately, it’s not entirely new ground (no pun intended). It does not require a fundamentally new approach. Orbital debris is really just pollution. Plain and simple. We need to treat it that way and employ similar successful tools that we have used here on Earth to clean up our rivers, forests, and air quality. And we should stimulate an economic environment that harnesses the power of innovation and capitalism to solve it permanently. This is our path to a sustainable future in space.

It happened when we weren’t looking.

For many years, those of us in the space community would attend conferences, sit on panels, and talk gravely about the problem of orbital debris. Everyone agreed that someday, irresponsible behavior in orbit could limit our access to space.

We even indulged in thought experiments like the “Kessler Syndrome”, where a collision in orbit could cascade into a chain reaction, annihilating every satellite, and creating a giant cloud of debris that would encircle the Earth, forever trapping humanity to an entirely terrestrial destiny.

But…, we never actually did very much about it. You see, space is really big, satellites are relatively small, and Earth orbit was mostly empty. So, it was always a problem for the future.

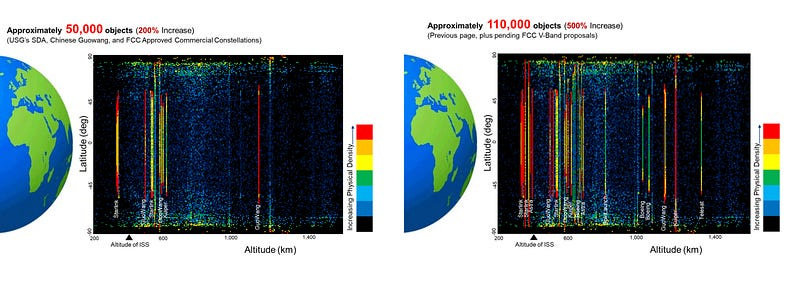

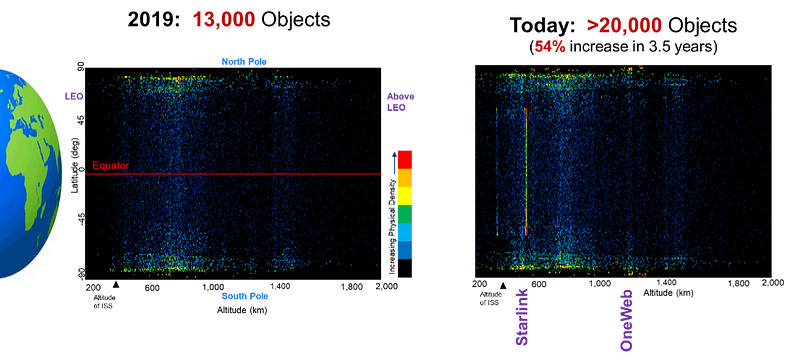

Guess what? The future happened about three years ago when nobody was looking. Satellites got smaller and smaller until it became practical to launch dozens at a time and, with thousands on orbit, to create global, high speed internet systems in the sky.

This is a game changer for access to information. To be high speed, however, these constellations must be in Low Earth Orbit (LEO), where there is literally “less space”, further intensifying the issue.

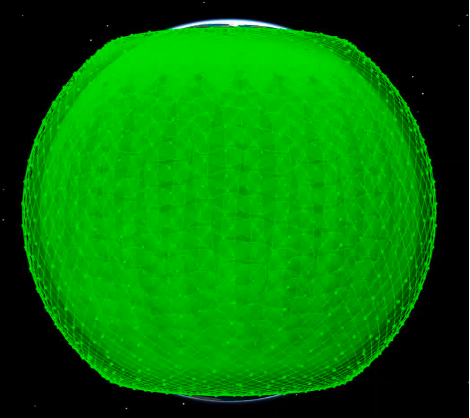

And LEO is becoming more crowded every week. In fact, we have more than doubled the objects in orbit since 2019, with many more on the way.

Space has become integral to our daily lives. Navigation, banking, agriculture, global commerce, national security, and climate monitoring are all now entirely dependent on space.

Doing without space is NOT an option.

Having global, low latency, high speed internet is an awesome future that will benefit millions of people worldwide. Having thousands of dead spacecraft, expended stages, and various other debris and detritus floating around Earth, would not be so great.

That outcome would threaten the bright future we just described. The emerging high-speed internet PLEO constellations would be the most vulnerable to an environment of unmanaged orbital debris. We need to catch up and get ahead of this problem.

Now is the time to get serious about managing orbital debris.

What is orbital debris and why is it pollution?

Well, I’m glad you asked. The answer is in the question. Orbital debris is… “debris”: uncontrolled, discarded trash floating in space. It fouls the common orbital environment just like terrestrial pollution.

Toxic chemical fumes leaving a smokestack don’t hover over the factory’s parking lot. They drift away affecting the neighborhood or even communities far away. The same is true for spills, ground water contamination, and trash dumping. Orbital debris is just like that. It orbits the planet, affecting everyone’s use of space.

Unlike a (heaven forbid) damaged airplane or ship, an uncontrolled object in space does not immediately leave the domain. It continues to circle the Earth while its orbit slowly decays. Eventually, it encounters the atmosphere and reenters. Depending on its altitude, that might be a few weeks. A bit higher and it’s a few years. Higher still and we are talking about decades, centuries, and even millennia. (Wow! That escalated fast).

The last thing we want is for LEO to become the “great Pacific garbage patch” (gyre) of space.

So, why does all that matter?

Space is an environment like the land, sea, and air, just a bit higher up. Pollution in space will render the night sky unsightly, but it could also make Earth orbit unusable.

While my terrestrial pollution analogy is pretty accurate, there are a couple of things unique about space. The first is that nothing is still. Remember that everything, everywhere, is always in orbit.

Objects in LEO are moving at over 17,000 miles per hour. Let me put that into perspective for you. An average bullet travels around 1700 mph. Objects in LEO are traveling ten times faster than a bullet!

A dead satellite, bolt, or some other general hunk of debris is not like a soda can, gently drifting along in the Pacific gyre. It’s a “hypersonic” cannon ball careening through orbit.

If a piece of debris encounters another object in a crossing orbit or, worst of all, hits another object traveling retrograde (the opposite direction), they will both be obliterated, creating a large debris field of smaller cannon balls still “zinging around’ in even less organized orbits. (Not a good thing).

If debris collides with a satellite inside a mega constellation shell, there isn’t much free space to work with.

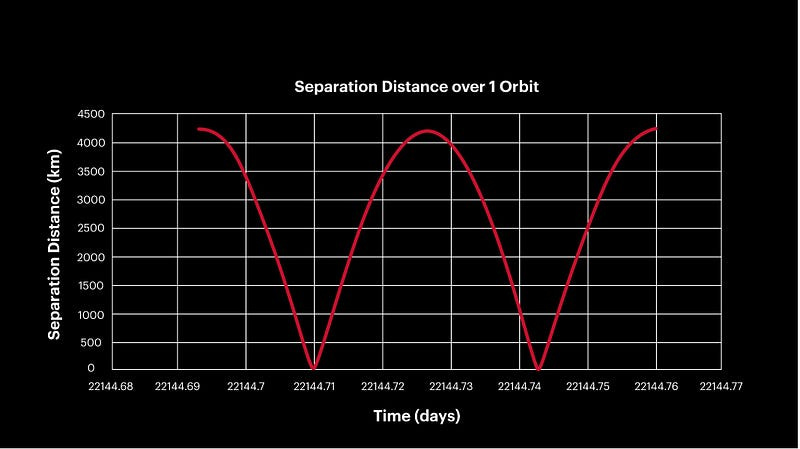

Each satellite in a LEO mega constellation (sometimes called a proliferated LEO, or “PLEO”), will have around sixty close approaches each day. Two birds will close within around 24 km of each other over and over, all day long.

While 24 km might sound like a lot here on the Earth’s surface, in LEO, that means they are only missing each other by 3 to 5 seconds each time! An orbital debris cloud created inside a PLEO shell could do significant harm to the constellation.

The other important difference is the inherent global reach of orbital debris. While certain forms of terrestrial pollution have global effects, like greenhouse gases, many forms of pollution stay local. They foul a river, or a neighborhood, or a regional water table. There is NEVER any such locality for orbital debris.

Every piece circles the entire globe. In, LEO, that happens every 90 minutes. Orbital debris is inherently global and international. One bad actor will affect all of us…

Kessler syndrome is no longer just a thought experiment.

OK, I get it orbital debris is bad. So, what do we do about it?

Thanks for asking. I just happen to have an idea or two on that. I recommend that we do three things.

Step 1: Treat Big Spills Like Any Other Environmental Disaster

We should outlaw, fine, and assign financial responsibility for major spills (like we did for the Exxon Valdes and the BP Deepwater Horizon incidents). Figure 6 below shows an example of two real events just like these, that happened in space.

Note that the U.S. destruction of a dead, but fully fueled, satellite was conducted at a very low altitude, below any other spacecraft, so that most of the debris reentered within hours.

By contrast, hundreds of objects are still in orbit two years after the Russian anti-satellite (ASAT) demonstration and thousands of high velocity “cannon balls” continue to orbit Earth five years after China’s ASAT test. China’s debris field will continue to pollute LEO for decades, slowly descending through the orbits of both the International Space Station (ISS) and nearby PLEOs.

Russia’s and China’s actions were undeniably irresponsible and akin to any large-scale environmental spill here on Earth’s surface. Future international law should extend the EXISTING terrestrial legal regime above sea level to encompass the space domain. This would apply to governments and commercial entities alike, as it does now, here on the surface.

Step 2: Stop Making More

Now that we have addressed the issue of egregious behavior, let’s tackle the more subtle issue of encouraging responsible stewardship.

It turns out that we have an effective model here as well: Carbon Credits. Under this system, countries have committed to goals for greenhouse gas emissions. They then license regulated commercial activities against these goals, driving applicants to generate or acquire positive credits, often called offsets, to obtain licensing for an activity that creates emissions.

In a few situations, this has proven to be a little tricky here on Earth because estimating how much atmospheric carbon is released by a given activity, as well as how much is sequestered by other actions, can be difficult to accurately measure.

That is not an issue is space. Orbital debris above a certain size is readily, and currently, catalogued on a daily basis via ground-based radar.

I would propose that we apply the same strategy here. Begin with the USG’s Orbital Debris Mitigation Standard Practices Guide (ODMSP). This calls for end-of-life satellites and expended stages to be either actively deorbited immediately, raised to a designated “junkyard” storage orbit, ejected entirely out of Earth orbit into a heliocentric (sun) orbit, or placed in an orbit that will naturally reenter in 25 years or less.

The first three elements are fine, but the “25 year rule” will soon become obsolete as LEO becomes home to thousands of PLEO satellites, packing into their thin, dense shells. So, we need to raise the bar here.

Using the Carbon Offset model, we would task the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) licensing bodies to set a standard of net neutral debris generation. Under this policy, we would ask that any object above a certain size that is left to naturally decay, should require Orbital Debris Credits.

I suggest starting at the 10 cm threshold currently tracked and catalogued. (These are the “cannon balls” of orbital debris. Smaller debris objects are still very dangerous “bullets” that will also need to be addressed over time as this model matures in practice.)

The bigger the object, the bigger the number of credits required. The longer it will take to deorbit (as assessed by its altitude), the bigger the number of credits. The more crowded the orbits below the object, the bigger the number of credits.

You get the idea. This approach acknowledges that not every piece of debris has the same impact to the environment. Fewer, smaller, lower debris, in less crowded regions, are less harmful.

If operators deliberately elect to perform uncontrolled and untargeted reentry, then they should also become financially responsible for any collisions they create and would generate additional negative credits for the new debris they caused as a result.

Step 3: Stimulate a Debris Cleanup Industry

The obvious question that you are no doubt asking yourself by now is, “Where do all these positive credits come from?”

Great question!

So as not to prematurely choke off the existing and vibrantly growing space economy, we should award a modest number of credits to operators who are already practicing good stewardship.

Placing an asset at the end of its life in the designated junkyard or heliocentric orbit would generate a small number of positive credits. Performing controlled, but gradual reentry would award more. An immediate reentry would generate even more credits.

All positive credits would be real and transferable property. In other words, the owner of an Orbital Debris Credit could sell it to another company in need of enough credits to obtain their license. Thus, we have created a marketplace eager to earn and sell Orbital Debris Credits.

To jump start this, we would begin awarding positive credits for a handful of years before the licensing regime comes into force.

Now, we don’t want to stop here because all we have done so far, is to drive the space industry to stop making new debris. What about the debris already there that needs cleaning up? Not to mention the capability to clean up after mishaps?

We will want to limit these “good stewardship credits” so that there is a mild scarcity. This will do two things. First, it will drive the price up, thus applying economic pressure to become a good steward. Secondly, it will create a need for some other way to create positive credits beyond just limiting the debris you generate yourself.

Viola! The birth of a “Debris Salvage” industry. To enable this, we would declare that any object abandoned for more than some length of time, say two or three years, is available for salvage by a second party. This will create a strong economic incentive for innovative companies to develop ways to capture and reenter other people’s debris.

Just like before: more credits would be earned for removing bigger objects, more credits for higher orbit objects, and more credits for faster removal.

I would also take this a step further. The salvage and repurposing of debris should earn more credits than simple reentry. This would encourage recycling of assets and materials already in space, thus reducing the number of new objects introduced into space.

Thus, we have created a space environmental cleanup industry.

And it was simply done via three actions:

1. Encourage good space environmental stewardship via FAA and FCC licensing.

2. Allow the earning, ownership, and selling of Orbital Debris Credits/Offsets.

3. Recognize the right to salvage and own abandoned orbital debris.

All without a cost to the taxpayer and with the added benefit of creating an entirely new space industry along with the jobs, innovation, and wealth it will create.

But what about bad international actors?

That is a very astute question to ask. Earlier, I advocated extending existing international environmental laws into space. But part of the basis of these existing laws are bilateral and multilateral agreements and treaties. Creating the terrestrial regime we currently enjoy took years of hard diplomatic effort. Even just extending this regime a few thousand miles straight up will also take time. This needs to happen, but what do we do in the meantime?

Economic Leadership.

The United States has a soft power that would be ideal within the largely economic model we’ve just discussed. That is the strength of our economy. Or, to put it in blunt terms, “If you want to do business with the U.S., the largest economy in the world, you must comply with our space environmental standards.”

This is very different than asking China to clean up their own domestic mining, fossil fuel production, or coal use. Space pollution effects the US, and everyone else, directly and immediately, no differently than if a foreign polluter dumped trash in Yosemite National Park.

We could mechanize this by assessing a company exporting into the U.S. or with a U.S. footprint for the presence of “beneficial ownership” by a foreign polluter. You might be surprised to learn that as little as 5% can give a share holder significant control within a company. I would suggest setting a value close to that as the threshold for liability.

If the foreign entity is also a polluter, via either a purely commercial entity or state-controlled business, then financial responsibility would attach to them through their entity doing business in the U.S.

If they are merely short on credits, then they can buy them like anyone else or be fined the equivalent market value. These entities will either pay, become good stewards, or be driven away. I would not consider the last outcome regrettable, given their poor stewardship and bad practices.

America has many natural allies in the cause of sustainable space. ESA’s Debris Mitigation guidelines, the World Economic Forum’s Sustainability guidelines, and the UK’s Astra Carta initiative are great examples. While the US would have significant influence all on its own, if other, like-minded nations adopt similar policies, the impact would be greatly multiplied and become irresistible.

These would be rapid, unilateral actions taken to stem the potential crisis while a broader international space environmental law regime is established.

We’ve done it!

By setting reasonable standards for licensing and with a stroke or two of the policy and legislative pen, we have defined an elegant and economically beneficial solution to what has become an urgent environmental problem… in space.